6 Best Practices for UX Knowledge Management

The Power of Knowledge Management Part 2

by Maria Taylor

The Power of Knowledge Management: Part 1 Recap

Effective UX knowledge management is essential for organizations aiming to improve collaboration, streamline processes, and drive innovation. By ensuring that research, design, and development knowledge is accessible and actionable, UX teams can deliver better outcomes faster. In this post, we explore six best practices for implementing and optimizing UX knowledge management.

As Victor Yocco highlights in his article on growing UX maturity in organizations, UX success depends on fostering a culture that prioritizes continuous learning and shared understanding. Building on these ideas, this article outlines six best practices for UX knowledge management, helping organizations optimize their processes and deliver better outcomes.

In our previous article, “Unlocking UX Success: The Power of Knowledge Management,” we explored the key challenges UX professionals face and how effective knowledge management can address them:

- Doing More with Less: Increasing budget, resources, and time constraints require team members to handle more work with inflexible deadlines.

- Improving Collaboration and Communication: The shift to remote work has heightened the need for better digital collaboration and communication within and across teams.

- Scaling Research and Design: There is a need to continue scaling research and design processes, tools, and artifacts to commoditize where possible, allowing teams to focus on complex challenges.

By managing UX knowledge effectively, we can overcome these challenges, improve transparency and accountability, democratize research and design, and leverage AI and automation for a competitive advantage.

In this post, we’re talking about best practices that are necessary to effectively manage UX knowledge, ensuring it is accessible, usable, and impactful for driving innovation and improving collaboration within organizations.

Key Takeaways from this article

- Engage the Right People: Involve key roles like UX Knowledge Managers, Knowledge Contributors, Knowledge Champions, and IT Support Staff to ensure comprehensive knowledge management.

- Support Both Explicit and Tacit Knowledge Management Processes: Implement structured processes for capturing, processing, and sharing explicit knowledge, and foster environments for informal tacit knowledge sharing.

- Turn Artifacts into Knowledge Assets: Enhance knowledge artifacts by providing rich context, making them easily findable, consumable, and usable to maximize their value and adoption.

UX Knowledge Management Best Practices

If you’re on the road to establishing UX KM practices for your org, you know it’s about more than just storing UX assets. It’s about activating knowledge management to maximize the value and impact of your organization’s collective knowledge.

Best Practice 1: Engage the Right People in UX Knowledge Management

Victor Yocco’s work emphasizes the importance of aligning roles and responsibilities to build UX maturity within organizations. Similarly, successful UX knowledge management depends on engaging the right mix of roles, from knowledge contributors to IT support staff. When it comes to UX knowledge management, the following roles need to be involved:

- UX Knowledge Managers – This role is the KM process owner, knowledge harvester, documenter, cultivator, and enabler. These managers should be members of the DesignOps team (e.g., design system lead). Depending on the size of your organization, this can be a fractional responsibility shared across one or more roles. And, as your organization matures and knowledge management tools and processes grow, along with the quantity of knowledge being managed, it could eventually make sense for this to become a full-time dedicated librarian/knowledge manager role.

- Knowledge Contributors – This group is made up of the subject matter experts doing UX work, UXers supporting product delivery, and the operations teams supporting them (e.g., the Design system team). It also includes those collaborating and contributing to UX work, such as UXers, UX leads, Product/project managers, Developers, etc.

- Knowledge Champions – Knowledge management champions use their leadership role and skills to encourage and advocate for adopting knowledge management best practices. They help to enable the cultural change necessary to get people excited and bought in. It is important to have champions in the C-Suite and from all parts of the business; they remove obstacles and help ensure knowledge is getting where it’s needed.

- IT Support Staff – Whatever tools you use to manage your explicit and tacit knowledge, you will need IT support to manage the technical infrastructure, databases, and other tools used to store and retrieve knowledge. Any tool you select will need to be vetted and approved by IT support, so start building lines of communication early.

Formally identifying and acknowledging the importance of responsibilities will help individuals start seeing themselves as knowledge stewards and more readily accept the responsibilities.

Best Practice 2: Support both explicit and tacit knowledge management processes

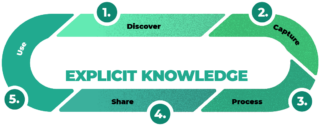

The process for managing explicit knowledge includes the following steps:

- Discovery – Identifying knowledge gaps or available knowledge that hasn’t been documented

- Capture – Exactly what it sounds like – documenting the critical information

- Process – Cleaning it up, making it repeatable and reusable

- Share – Disseminating the knowledge for wider access

- Use – Putting the knowledge into practice and ritualizing it’s use

The process is straightforward. There are many different variations of this diagram available on the web, but they all have some flavor of these steps.

The first 3 to 4 steps are the most well-understood, and those involved in this process feel most comfortable. However, the most significant difficulty lies between sharing and using (steps 4 and 5). We will share what those hurdles look like and how to move past them a bit later.

There are somewhat similar but different processes for managing explicit and tactic knowledge.

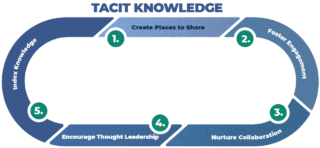

Tacit knowledge is typically shared from person to person rather than from artifact to person. Common tacit knowledge-sharing vehicles include Interviews, work collaboration, mentorship, workshops, forums, and community. The tacit knowledge management process includes the following steps:

- Create a place for informal knowledge-sharing

- Foster engagement – collaboration and communication

- Monitor and nurture

- Identify and encourage subject matter experts (SMEs) who have that knowledge to share it with others

- Index knowledge – Improve findability and determine the potential for further codification

The tacit knowledge management process also gets harder the further you move along the steps in the process.

Tacit knowledge sharing – influencing factors

There are four factors that greatly influence whether or not tacit knowledge gets shared. Keep in mind that Tacit knowledge is typically shared from person to person rather than from artifact to person, so it has a very human element to it.

- TRUST: Trust is an important prerequisite for tacit knowledge sharing because, without trust, people are not willing to be vulnerable and to share. People build status based on their knowledge and need to have trust to feel comfortable giving others their knowledge-based power. Trust is a major enabler for sharing tacit knowledge.

- SELF-EFFICACY: Self-efficacy – is one’s confidence in one’s ability to achieve a specific performance goal, and having a higher level of self-efficacy builds one’s confidence in one’s ability to share knowledge with others and, therefore, impacts one’s motivation to share. If people believe in their ability to share knowledge, they will be more motivated to share it with others. Self-efficacy is another major enabler of tacit knowledge sharing.

- IT SUPPORT: This is another critical enabler, as it involves ensuring that the proper infrastructure is in place to facilitate frictionless collaboration and communication across the organization.

- KNOWLEDGE TACITNESS: Knowledge tacitness refers to the degree of difficulty in articulating and transferring knowledge. The more tacit the knowledge, the harder it is to articulate and share. But not all tacit knowledge is completely tacit—there are degrees of tacitness.

These influencing factors are discussed in greater detail in a study by Juarun Wang and Jin Yang called, An Empirical Study of Employee’s Tacit Knowledge Sharing Behavior.

Best Practice 3: Turn Artifacts into UX Knowledge Assets

Explicit knowledge artifacts

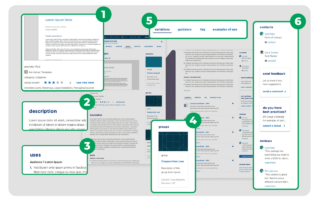

Artifacts are the outputs of the KM process and are the heart of a standard knowledge management system. Some examples include playbooks, research reports, methodology or process documentation, role descriptions, or brand guidelines. Anything that can be documented and has somewhat durable value. But it is not enough to present the artifact itself; you must make it a KM asset. What does that mean? It means wrapping it up with all the necessary information to make it findable, consumable, and usable.

This is an example from a project we did two years ago. Specific details have been hidden by turning it into lorum ipsum, but you should still get the gist.

(1) You have a preview of the artifact itself, how well it has been rated by others who have used it; (2) a description of the asset’s common use cases; (3) you have information on its intended use, (4) a list of audiences for which it is intended to serve, (5) a list of other variations on that artifact, guidance documentation, frequently asked questions (FAQs) and examples others have submitted that use this artifact. (6) There is contact information for 1-2 individuals that can help you learn how to use it. You can submit feedback or a best practice example and write reviews. Providing this richer context makes it much more likely that a knowledge artifact is understood and will be adopted. These mechanisms also help to make the knowledge management process easier for those in charge while keeping the content evergreen and relevant for those who need it.

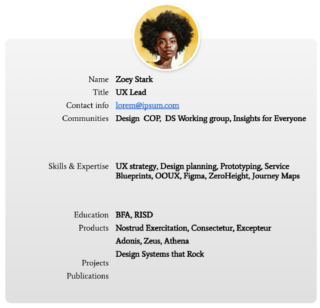

Tacit knowledge artifacts

Tacit knowledge often cannot be represented in an artifact, but you can create a wayfinding knowledge container that points you toward where to find it. Employee profiles (a directory), searchable forums or communities, and comments fields are all wayfinding sources. Let’s use employee profiles as an example….If you create robust employee profiles, then it can help people find others who are likely to have the tacit knowledge they are interested in.

Looking at the example profile of Zoey Stark provided, in addition to Zoe’s standard contact information, we know what communities of practice Zoey belongs to; we see her skills and expertise, the products and projects she has worked on, and any publications she has written. With this information, I have a good idea of what she is knowledgeable about. Building richer (and more searchable) profiles will ALSO provide access to a broader and more diverse set of perspectives to draw upon.

Best Practice 4: Select the tools people want to use

Tools for managing explicit knowledge

Effective knowledge management is as much about the system used to store the information as it is about the knowledge itself. You might have great stuff to share, but if it’s difficult to find or use, then all that great information doesn’t help anyone.

Typical explicit knowledge management tools include:

- Corporate Intranets

- Wiki

- Document management systems

- Content management systems

- Databases/Data Warehouse

I’m sure you are all pretty familiar with these types of tools. When identifying potential KM tools within your organization, if there isn’t a required tool, use whatever tool/system has the lowest barrier to entry and that people will use.

Tools for managing tacit knowledge

Managing tacit knowledge is about creating places that enable sharing from person to person. Common tact knowledge management tools include:

- Social networks

- Communities of practice

- Forums

- MS Teams, Slack, SharePoint communities

- Jira, Github

- Company directory

These tools help employees coordinate and quickly share knowledge. Don’t expect to find a one-size-fits-all solution, as you will probably need to leverage more than one tool. When selecting the tools you want to start with, make sure they support discovery methods (e.g., enable keywords, include canned queries, and make sure you have powerful search capabilities).

In most organizations, there are a variety of tools available and used to store and manage both explicit and tacit knowledge. User experience knowledge must be accessible and easy to find for anyone in the organization, not just the people performing UX work, rather than creating a centralized repository for explicit UX knowledge and hoping that others will come to it. It may be better to start by identifying the core KM tools and repositories the rest of the business uses and figuring out which UX knowledge needs to be inserted into the most relevant locations. Because UX knowledge will likely be spread across tools and systems, the most important thing is to develop a common information organizing structure and a set of taxonomies that can be applied consistently across tools and systems. These structures and taxonomies can also be applied in your tacit knowledge-sharing tool.

Best Practice 5: Activate learning outcomes

Ultimately…it’s not just about knowing more…it’s about doing more with what you know…or what you’ve learned. At this point, I’m transitioning a little bit outside the realm of knowledge management and treading into learning enablement – but if we’re to be successful, we have to go there – for the exact reason this quote covers.

Activation doesn’t start at the end of the journey; it has to be addressed along the way. There are a handful of factors that need to be considered as you move through the KM Process:

“The end of the journey isn’t just knowing more; it’s doing more.

”

– Julie Dirksen, Design for how people learn

-

- Knowledge

- What information is needed?

- When will it be needed?

- In what formats?

- Skills

- What needs to be practiced to develop the needed proficiency?

- Are there available opportunities for practicing?

- Motivation

- What is the cultural attitude toward the change?

- Will there be resistance?

- Knowledge

-

- Habit

- Are there any new behaviors or habits required?

- Are there existing habits that need to be unlearned?

- Environment

- Are there any environmental factors that are either preventing or supporting success?

- Communication

- Are the goals related to expected learning outcomes being clearly communicated?

- Habit

This addresses the earlier gap when discussing knowledge management processes, specifically the difficulty of moving between steps 4—Sharing and 5—Use in the explicit knowledge management process. The concepts laid out above are from Julie Dirkson, a fantastic expert on learning enablement, in her book Design for How People Learn.

Best Practice 6: Account for organizational context

Let’s talk about context – there are several contextual factors that can impact the success of your knowledge management efforts:

-

-

- Culture—Is there a culture of learning within your organization? Are Individuals encouraged to see themselves as knowledge stewards and subject matter experts?

- Structure – Team vs. Business Unit vs. Org Wide—Within these lenses, knowledge artifacts, processes, and systems might need to be different. We have to be aware of how to navigate these differences and how to support people working within them. For example, there are types of knowledge and documentation that are only relevant to a specific product team context.

- KM Approach – Is KM an org-wide goal that has an org-wide approach? Where are there clear examples and expectations of where info gets stored and what your knowledge artifacts look like? Or is it happening in pockets of the organization where each group is doing its own thing?

-

Lastly, there is Knowledge Origin—top down and bottom up—which depends on the source of the knowledge or expertise. Some knowledge is only trusted if it comes from the bottom up—the experts themselves. Other types of knowledge can be driven top-down. You need to know which point of origin will bring success and extract the knowledge from that vantage point.

Best Practice Recap

- Knowledge is the lifeblood of any organization.

- Knowledge management is a well-established concept.

- The methods and tools we use to manage knowledge evolve.

- A successful knowledge management solution needs to be tailored to the needs and the culture of the organization

Best Practices

- Engage the right people

- Support both Explicit and Tacit processes

- Select the tools people want to use

- Turn artifacts into knowledge assets

- Activate learning outcomes

- Account for organizational context

As Victor explains in his article, UX maturity grows when organizations embrace a culture of shared knowledge and collaboration. By adopting the six best practices outlined here, your team can accelerate its journey toward a more innovative and knowledge-driven future.